An international award of Japanese origin, the Kyoto Prize is presented to individuals who have made significant contributions in the fields of science and technology, as well as arts and philosophy. Kyoto Prize laureates are those who have made an extra effort to plumb the depths of their chosen fields and profoundly inspired the scientific, cultural, and spiritual betterment of humankind through their achievements. In this series of “Unearthing the Words of Kyoto Prize Laureates,” we will interview the past laureates of the Kyoto Prize and take a closer look at the words that they delivered at their Commemorative Lectures to get to the heart of their unique ideas, thought process, and attitudes as inquirers. In this installment of the series, we had the pleasure of interviewing Joan Jonas, the 2018 Kyoto Prize laureate in the Arts and Philosophy category.

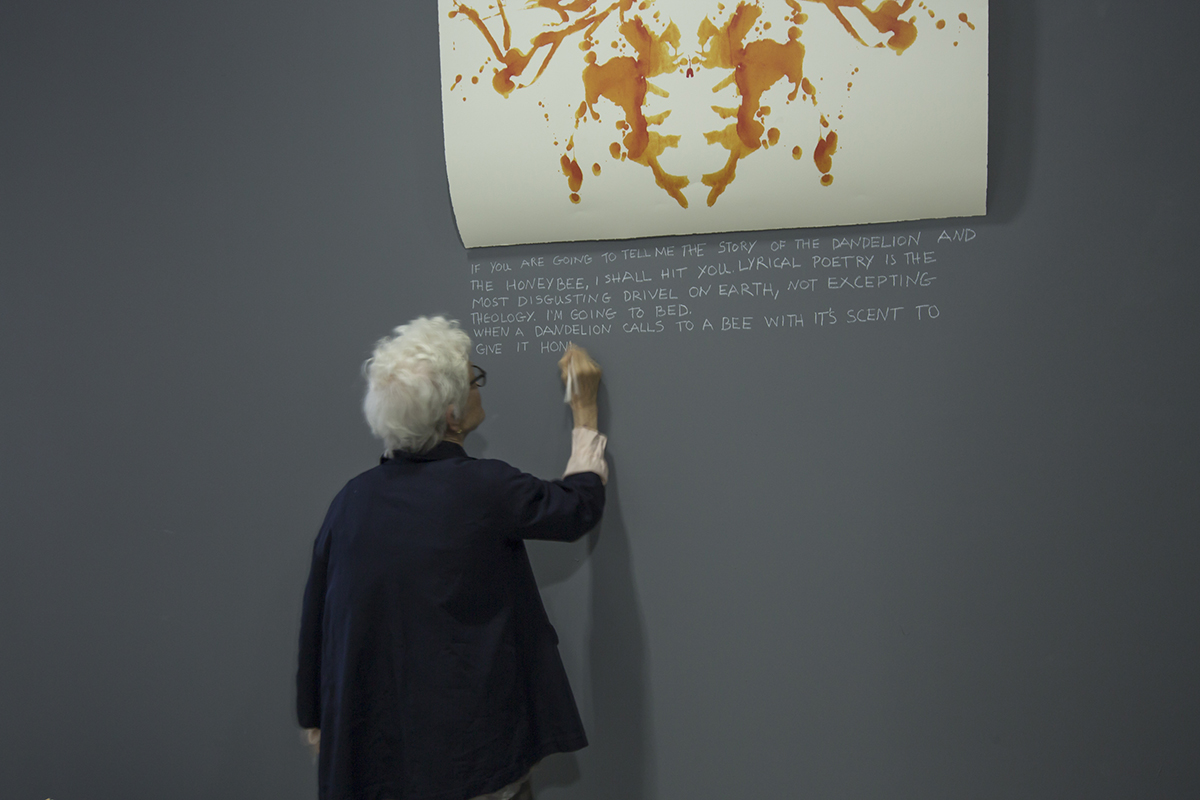

Joan Jonas

Artist. Professor Emerita, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. As one of the pioneers of new artistic expression, Jonas integrated performance art and different media in the early 1970s. She has been pursuing exciting relationships between performance art and new digital media. She represented the United States at the 56th Venice Biennale in 2015. She held her retrospective exhibition at Tate Modern in the UK in 2018. Read more

Previous articles in “Unearthing the Words of Kyoto Prize Laureates”

Nishimura: In your Kyoto Prize Commemorative Lecture, I remember you mentioned that you studied poetry at graduate school and it has had a large impact on your artwork. What does poetry mean to you?

Jonas: By literature, I mean prose in the form of novels and poetry altogether. But poetry has a unique and very different structure from the form of prose and novels. I always loved to read all kinds of stories. I think I’m kind of a storyteller on one level. Over the years, however, it has become part of me, while doing my work, that poetic structure is like the basis of our lives and the way we look at the world. As artists, we translate it into a poetic form. So the fact that poetry itself has a structure and its condensed form interested me. In other words, there are different ways of saying things.

When I shifted from making sculpture and studying art history to concentrate on performance, I had to develop my own language and find a way to structure my work. In other words, anything you put out there has to have a form. The form is very important. For instance, I was inspired by poetic form and film. I based my early structures on the form of poetry and film, and I still do. Those have become embedded in my process.

Nishimura: Very fascinating. Poetry doesn’t always follow correct grammar. Yet, some meaning is born by layering things and words. Could you tell us a little more about how such a structure of poetry comes into play in your artwork?

Jonas: When I began to make artworks in the 60s, I began by stringing disparate things together. For instance, in a montage, you can put two disparate images together to come up with a third meaning that is derived from the changing combination of those two elements. I think the different images come together in different ways as the viewer or reader advances through a film or text. I can never know how people might interpret my work, but I do try to be clear in my thinking and expression.

I’ve quoted quite a bit of poetry in my work. For instance, Borges was my first inspiration in my performance work. His stories are so fantastical that they go into another realm of prose and his work has a poetic structure. I took all the quotes about mirrors from his book Labyrinths and made a piece based on the mirror. That was the influence of Borges and his writing. Mirrors became my first metaphor and my first prop. From the beginning, in the layering of my work, it has interested me to refer to the structures of film, poetry, music, visual arts, and how they can relate to one another.

Many of these ideas of working with the form of poetry and film started in the late 60s. I wanted to develop what I thought of as my visual language. I began to layer things, which became more complicated as I began to work in time-based media. I think I mentioned the work of American Imagist poets and my interest in Irish literature and poetry in the Commemorative Lecture. But of course I’ve worked with different poets over the years.

Sugimoto: In the process of creating performance art, you rehearse it many times and work hard on every detail. Yet when you actually perform, you seem not to be in perfect control, but rather let things happen and incorporate them as they develop. What do you think about the balance between developing a solid structure of the work and allowing contingencies in it?

Jonas: You’re absolutely right. I rehearse my work and I perform it in the way I’ve rehearsed repeatedly. My style is a little looser than some other theater groups, so it could take me a few more seconds to move from here to there or I may add a little movement. It may look like I let things happen but I really don’t.

A lot of my movement has to do with working with props and moving objects, and that’s part of my visual language. I collect objects and props and use them in certain ways. However, I don’t like to explain my work and talk about what it means. I can talk about the sources, where it came from, and what the general idea is, but I don’t like to explain every detail.

I think almost everyone improvises, loosely putting things together, moving in different ways and experimenting when they are developing work. Then one comes up with his or her own approach to something. Of course, when I began working in performance, I began with improvisation. Improvisation is part of our existence and a way for us to survive.

When I collaborated with Jason Moran, a jazz musician, we improvised. In the beginning, Jason would look at the edited video that formed my backdrops as well as the subject matter and situation. He would bring some examples of music. I would listen and choose what I like, and then he would work out a soundtrack. I also was inspired by his music so I could find new ways to move. I had some instruments like bells and toys and he played the piano, and we performed together. But all improvisation is based on certain themes. It’s true that I have been a little looser and improvising a little more lately, but it’s not my basic language in live performance. Each time I repeat a performance, I find ways that I can edit or improve it.

Nishimura: When you are performing live, how much do you imagine what is going on in the audience’s mind?

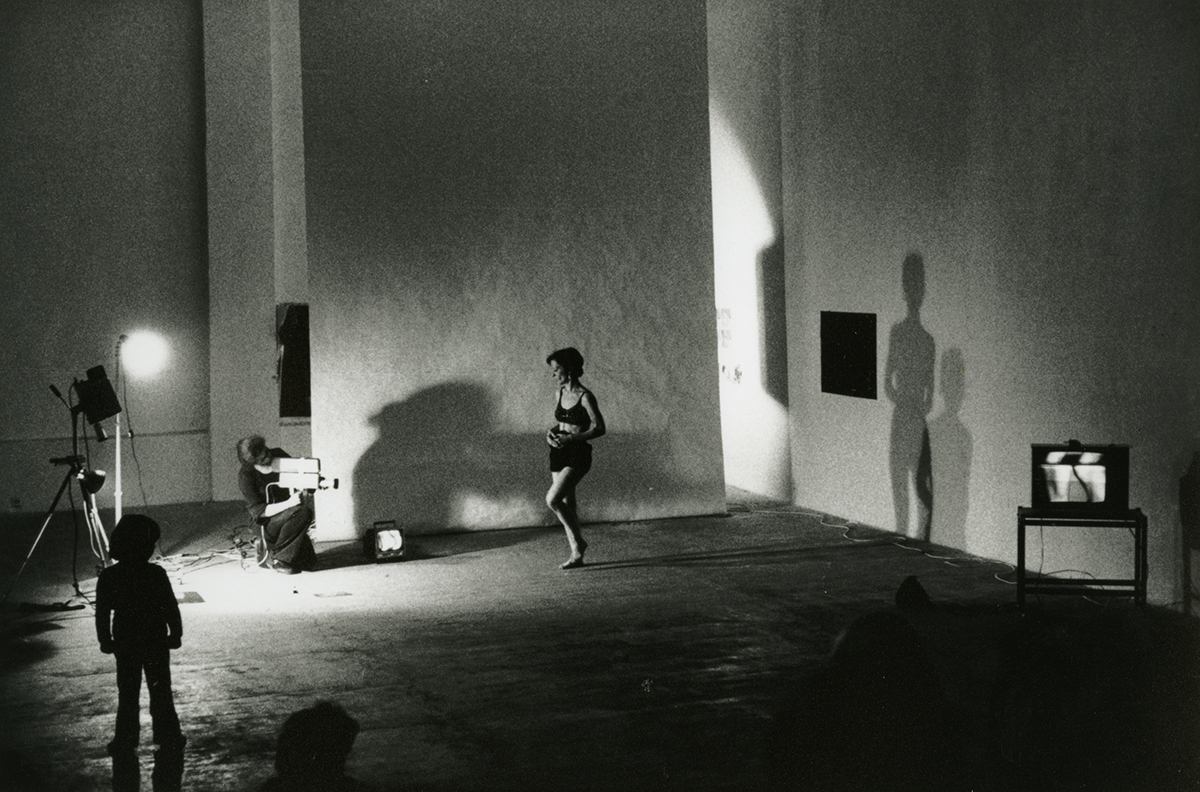

Jonas: I try to think about what the audience actually sees and hears and make that as coherent as possible. However, if I imagined what is happening in the audience’s mind, it would be very disconcerting. One of the reasons I don’t improvise in front of an audience is related to the way I develop my work. I am making images for the audience, but while I am working, I am my own audience. I constantly step out of my zone and look at what I’m doing. So the video recording has been very helpful in that way.

Of course, I know that, where there’s an audience, we all see things slightly differently. We all see the same things, but our minds process them differently. I am always curious about that. However, it would be too much information in my head if I imagined it while performing. I really have to concentrate on the present moment in a performance.

Nishimura: It seems to me that in your work, an image is left in the audience’s mind while the next image comes to life. Do you think of a structure in which the message of the entire work integrated in the end?

Jonas: Art is about communication. Before making performance, I studied art history and sculpture. By looking at the past (the history of painting and sculpture and other forms), we communicate and we are influenced by that past and other cultures. For instance, I was so curious about other cultures and the history of rituals that I researched these subjects.

In the beginning, I was asking myself, “why am I making performances?” “what is my place in my community?” And then I thought of my own work as ritual, not necessarily religious or spiritual but my own ritual. It is about doing something over and over again every day as you interact with your peer group.

I also went to as many dance and movement presentations as possible, starting in the early 60s. Why do we go and look at work? One reason we go and look at work is because it brings us together. We could talk about the reason why we do these works, why we get together and look at things together, and why we are in a community. We communicate to each other and the work communicates to us. This leads to an exchange of ideas.

Nishimura: I would like to ask a question about technology. One way to look at technology is to use it. Another may be to be inspired or instigated by technology. When you encounter a new technology, how do you develop a relationship with it in a way that inspires new artwork?

Jonas: Technology is defined as a device that alters things, the world and your perception. I looked up the term “technology” to find that “techniques for altering the human environment” was one of the definitions. I never thought of that before, but it fits in with my interest in using technology and also my whole way of thinking about my work. For me, technology is not necessarily electronic, it can be a mirror, the use of distance, and how that affects our perception. So what I want to do is to alter. My basic desire is to alter the way the audience perceives the space, the distance, the narrative.

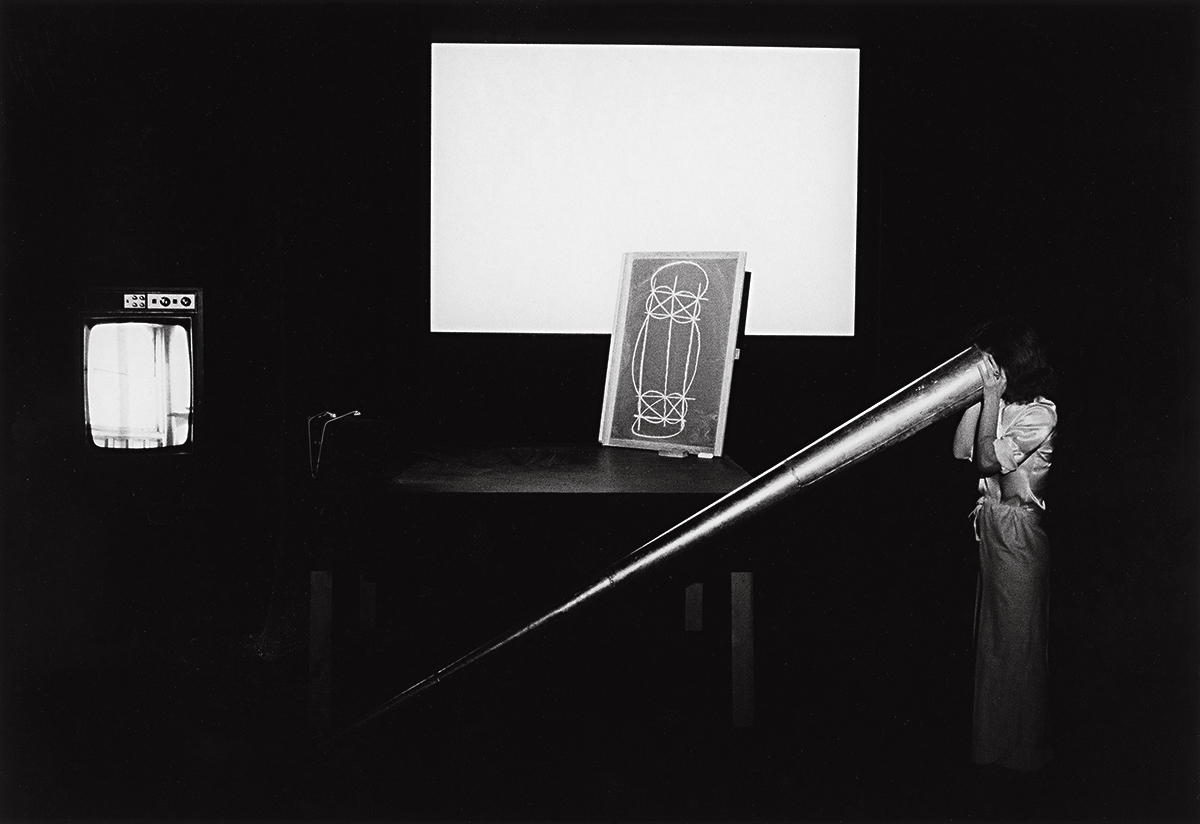

I made several performances with mirrors called Mirror Piece from the late 1960s to the early 1970s. In the performance, there are 17 people carrying mirrors and the moving mirrors reflect the space, the figures and the audience. The performers alter the way the audience perceives the space as they move very slowly with the mirrors. When I switched to video, I called it an ongoing mirror. It is true throughout my work that I deal with images and how to alter those images in the eyes of the audience.

Sugimoto: You do not make works in a single form of expression, but rather create pieces integrating multiple forms of expression, such as sound, motion, narrative, video and drawing. You also use props like mirrors and cones in multiple ways and enjoy collaboration with many diverse artists. What keeps you interested in integrating different things?

Jonas: When I began making art, I loved to cook. Food and cuisine is certainly a form of art making: when you put two elements together, a chemical reaction happens and you get a third, a taste. When I first started making the kind of work that I’m doing now, I thought of it in relation to cooking.

Through sculpture and art history to my present artmaking, I didn’t see a major difference between these forms. One could use the language of different forms such as poetic structure, filmic structure, or montage. In this way I found my own language, which didn’t exist at that time. However, boundaries were being broken down between the forms during that era. I was searching for a way for me to step into what they call “performance art.” As I had no experience in theater, I had to develop my own way of being a performer in front of an audience while learning at a lot of dance workshops.

Before I began to perform publicly, I was able to experiment and learn both from looking at the work of other dancers and by going to workshops.

At some point concerning the work, I say to myself, “OK, it’s finished.” It’s intuitive and each work comes to its own end. I’m always interested in going on to the next piece rather than going back and continuously altering what I’ve already done. Sometimes, certain developments and sequences are passed from one work to the next. The context or the new subject will change one’s perception of these sequences. They all look like my work, but the subject is changing. Sometimes the change is radical and sometimes it is obviously a gradual development.

Once when I came to the CCA Kyushu (Center for Contemporary Art Kitakyushu) in Japan, I made 100 fish drawings and called it They Come to Us without a Word. Then it led me to the work of the Icelandic writer Halldór Laxness in Reanimation, a work I performed in Japan and elsewhere. In this case, I was inspired by his references to nature. So one work leads to the next in this way.

Nishimura: It sounds to me that you pursue your expression with great precision and close attention to details. I wonder what drives such an attitude of yours. For example, many young artists as well as young researchers may struggle and wonder how far they should go in their pursuits. Do you have any thoughts in this regard?

Jonas: I think every young artist has to find their own way. There are thousands of ways to think of the word “precision.” For example, I’m doing a big installation show at Haus der Kunst in Munich now. I had a lot to think about throughout my stay here for a week: where is the projection shown in the space, where does the object go, or how is the sound functioning. Without paying attention to these details, the work will not exist.

Some young people may not be interested in the details. They want the general, the big movement, and they think the details come later by accident or through improvisation. For me, however, details are an integral part of the work. I have to continuously look at the work and make sure of each detail. For instance, the quality of the sound is very important as well as the qualities of the video projection. It’s also very important to get the right color in the video projection. Just as when looking at buildings and architecture, details are important with every art form.

Nishimura: I had an opportunity to talk to a Noh actor before. He said that the performance would be better if one single person in the audience appreciated the amount of training required to perform the piece. What role does the audience play in helping your work become what you imagine it to be?

Jonas: In a good situation, a performer can feel that the audience is fully attentive and totally involved. You have the experience of feeling “tonight’s performance went so well and the crowd was great!”

When I first started working as a performer, I’d have stage fright and get nervous. So I always had to imagine three or four people in the audience who really understood and liked my work. The audience and my relationship with them are different depending on the situation. For instance, sometimes, Italians tend to like talking during the performance, and intuitively accept inconsistencies and surrealist juxtaposition of images without asking a question. Sometimes, the Germans, on the other hand, have a lot of questions after you do a performance because they have a very logical way of looking at things.

Regarding my relation to the audience, all audiences are important. Some of my performances have to be seen in a small space because the audience wouldn’t be able to perceive it if it was held in a huge space. When I did a performance titled Reanimation with Jason Moran in Kyoto two years ago, sound and big movements were important to communicate with a huge audience. I enjoy and find it thrilling to have a big audience. I don’t let them affect the work but they make the work. The audience gives energy back to the performers.

Sugimoto: While studying poetry, you became interested in haiku, and you watched Japanese films such as Ugetsu Monogatari by Kenji Mizoguchi and works by Yasujiro Ozu. You also referred to your experience with Noh theater during your visit to Japan having an influence on your works including Organic Honey. How do you see the influence of Japanese culture on your work?

Jonas: I was so affected by the Noh theater and the Kabuki that some of their spirit certainly seeped into my work. The main thing is that I’m not interested in copying their real images in any way. I come from a Western tradition of theater, which is based on character development and drama. On the other hand, Noh is, as many other Eastern theaters, a musical performance of text, music and movement, or a dance theater in which the movement is very important. It attracted me so strongly that I felt it gave me inspiration and legitimacy in developing my own work.

When I first went to see the Noh in Kyoto, I didn’t always know the stories. But I could watch it and get pleasure simply from the visual elements and sounds. The Noh stage traditionally has large jars buried under the stage. It acts like a drum, and the sound resonates as the performers step on the floor. I also loved the way the Noh and the Kabuki used everyday materials, such as paper and sticks, and very simple structures as props and objects. It really affected me.

If you see my work, you will not necessarily think of a Japanese reference. The influence is very underneath and abstract. When I begin a new piece, I sometimes have no idea what I’m going to do and where to begin. In such cases, I look back at some of the books on Noh plays that I read a long time ago. Most recently, I made a poem by rearranging phrases and words from Noh plays and putting them back together again.

I’ll mention two concrete elements whereby Noh theater influenced me. One of the strong elements in Noh theater is the sound of wood hitting wood. After my visit to Japan in 1970 to see the Noh theater, that sound led me to use the wood block clapping to show the sound delay, which is part of the idea of distance in my outdoor performances such as Song Delay. Another aspect that influenced me was the use of masks. The ones I use are not all based on Japanese masks. For instance my first mask was a Canadian hockey mask. I collect masks. I have all different kinds of masks including masks from Mexico and other masks made of different materials such as metal screen. I have also used Japanese kimonos in my work over the years. The flexibility of the form and the beauty of the kimono is another element.

Nishimura: How does the switch from one phase to the next happen as you get inspiration from something, create a piece of work, and then begin in-depth research again?

Jonas: There’s not really a switch. It’s a slow development. For instance, when I began to work with video, the first thing I did was to set up the video camera and sit in front of it. Then by looking at myself on the monitor, I began to improvise with objects, masks, sound, and so forth.

My major work usually lasts a two-year period. I suppose this is one of the functions of performance: in presenting it, you’re forced to come to certain conclusions but it’s just part of the process. Then I do another version a few months later and develop it further. I keep taking parts out and putting them back into the work. You could call it my private world. That’s one way.

Another way is to work with a space. Space is very important. When I did a piece at Dia Beacon with Jason Moran, we worked for six weeks in the space, developing the work. One doesn’t have that chance very often.

In this case, I had done a lot of work to prepare for it. I spent a couple of years thinking about the content of this work, recording and editing video, and making backdrops. Then the next stage was to work with Jason to create sound and movement every day, using the background and structure of the script based on the content. Gradually, things came together and formed the piece of work.

On the other hand, I made a piece called Out Takes. What The Storm Washed In in 2022. I looked through all of my work with my assistant David Sherman and found sections that had never been shown in New York, or very few people have seen. As I put a series of video images together, a strange logic developed and it held them together. I made a performance out of that by playing them and thinking, “what will I do in relation to this one?” or “how will I segue this into that one?” These are just two examples: every work has a slightly different way of development.

Recently, I’ve been working in collaboration with dancer Eiko Otake. I can totally trust Eiko’s improvisation with me. I could easily step into a performance without knowing what she’s going to do exactly. I wanted to direct Eiko and we did a piece together. I brought my props and set up all the situations and Eiko, the very strong part of the piece, performed with me, responding to all of that. That’s another way of working. We’re going to work together again, but in a different way from the way that I have with other people. Maybe it’s a little bit like working with Jason, the composer.

Sugimoto: You’ve taught at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) for about 12 years. Having worked with many scientists, what are your thoughts on the roles of scientists and artists?

Jonas: The scientists are exploring the universe and the functions of materials. There are all kinds of roles for scientists. When I was at MIT, I was working in a very small art department. My students were either architects or scientists from other departments. I think scientists and artists have a great deal in common in the way they use experimentation to find the answers to certain questions. They explore the universe.

I only began to work in collaboration with a scientist in my more recent piece Moving Off the Land. It was commissioned by TBA-21 (Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary), which is working on the ocean theme. Moving Off the Land was a work that addresses a very important question that is present right now in our relationship with the environment. The ocean is a vast subject, but I had a way of dealing with it. I worked with marine biologist David Gruber who filmed fish in different ways using the cameras and lenses he developed. These cameras and lenses imitate the fish eye and can see the world as fish do. These cameras can see the luminescence that we can’t see but fish can.

David also let me use his footage he shot underwater. I combined that footage with my performers working in that context. For instance, the idea of a mermaid could be underwater in this beautiful footage of plants and animals. However, it’s quite a process for an artist and a scientist to come together and to work and share.

Sugimoto: Is it the pursuit of something that brings artists and scientists together to collaborate?

Jonas: It is not easy to bring artists and scientists together and make them want to collaborate. Making it possible, however, is their curiosities for exploring the universe in which we are living. In my case, I met David at a conference and became interested in his research. We still have a good relationship. Another scientist I work with is a specialist on rivers that run under the sea.

When I had an idea of a project in this area, he sent me sonar images of the undersea river system. Based on these images, I made 75 drawings. Making drawings from the ideas scientists give me is a translation of their work into visual form. Translation is very important for those who do not know what these sonar images represent. I think the translation can exist on its own.

This is a new development in my work, wanting to exchange with and learn from scientists. We never stop learning and researching. Learning about the planet, the oceans, and the underground rivers fascinates me. Scientists lead me to these subjects in completely different ways.

Nishimura: I practiced Kyudo, Japanese archery, when I was a student. My experience today was just like being in that space drawing a bow with intense concentration. Thank you so much for your time.

Click below to watch the YouTube video of Commemorative Lecture from 2018.

Previous articles in “Unearthing the Words of Kyoto Prize Laureates”

#1 Toyoki Kunitake: You’re Sure to Find a Breakthrough in the Process of Going Back and Forth Between “Abstraction” and “Materialization”

#2 Takashi Mimura: “Being of Service” Means to Be Needed and Appreciated by the Overwhelming Majority

#3 Takeo Kanade: The Habit of Returning to the Question “Why am I Doing This Research?” Is the Key to Reaching the Essence

#4 Tamasaburo Bando V: It is Only in Our Encounters with Others that We Can Convey the Ineffable

#5 Graham Farquhar: As Part of An Ecosystem, I Exist as an “Old Tree in a Forest”

#6 Edward Witten: Science Helps Us Understand the World Better

#7 Peter Raymond Grant, Barbara Rosemary Grant: Substantial Value in Connections Found Between Disparate Ideas and Facts

[About the interviewer]

Yuya Nishimura

Executive Director, MIRATUKU. Earned a Master’s Degree from the Osaka University Graduate School of Human Science. Built a cross-sector -business and -domain innovation platform, supports leading companies (about 30 annually) in creating new businesses, assists launch of R&D projects, designs future visions, and searches for future trends. Other positions include Innovation Designer, Innovation Design Office, RIKEN, Japan, and Specially Appointed Associate Professor, Social Solution Initiative (SSI), Osaka University MIRATUKU website

[About the writer]

Kyoko Sugimoto

Freelance writer. Earned a Master’s Degree in Media, Journalism & Communication, Graduate School of Letters, Doshisha University. Interviews researchers, business managers, Buddhist monks, urban designers on such topics as asylums, communities, and Buddhism. Authored Kyodaiteki Bunka Jiten: Jiyu to Kaosu no Seitaikei (Kyoto University Cultural Encyclopedia: Ecosystem of Freedom and Chaos), Film Art, Inc. writin’room