An international award of Japanese origin, the Kyoto Prize is presented to individuals who have made significant contributions in the fields of science and technology, as well as arts and philosophy. Kyoto Prize laureates are those who have made an extra effort to plumb the depths of their chosen fields and profoundly inspired the scientific, cultural, and spiritual betterment of humankind through their achievements. In this series of “Unearthing the Words of Kyoto Prize Laureates,” we will interview the past laureates of the Kyoto Prize and take a closer look at the words that they delivered at their Commemorative Lectures to get to the heart of their unique ideas, thought process, and attitudes as inquirers. In this installment of the series, we had the pleasure of interviewing Dr. Peter Raymond Grant and Dr. Barbara Rosemary Grant, the 2009 Kyoto Prize laureates in the Basic Sciences category.

──────────────

Previous articles in “Unearthing the Words of Kyoto Prize Laureates”

#1 Dr. Toyoki Kunitake: You’re Sure to Find a Breakthrough in the Process of Going Back and Forth Between “Abstraction” and “Materialization”

#2 Dr. Takashi Mimura: “Being of Service” Means to Be Needed and Appreciated by the Overwhelming Majority

#3 Dr. Takeo Kanade: The Habit of Returning to the Question “Why am I Doing This Research?” Is the Key to Reaching the Essence

#4 Tamasaburo Bando V: It is Only in Our Encounters with Others that We Can Convey the Ineffable

#5 Dr. Graham Farquhar: As Part of An Ecosystem, I Exist as an “Old Tree in a Forest”

#6 Dr. Edward Witten: Science Helps Us Understand the World Better

──────────────

Peter Raymond Grant

Barbara Rosemary Grant

Evolutionary Biologists. Professors Emeritus, Princeton University. Peter Raymond Grant and Barbara Rosemary Grant have conducted a long-term field study on Darwin’s finches on the Galápagos Islands for more than forty years since 1973. They demonstrated that rapid environmental changes cause natural selection, resulting in evolutionary adaptation. Both husband-and-wife Grants received the Royal Medal in Biology in 2017.

Read more (Peter Raymond Grant) Read more (Barbara Rosemary Grant)

Nishimura: First of all, may I ask you to briefly introduce your research?

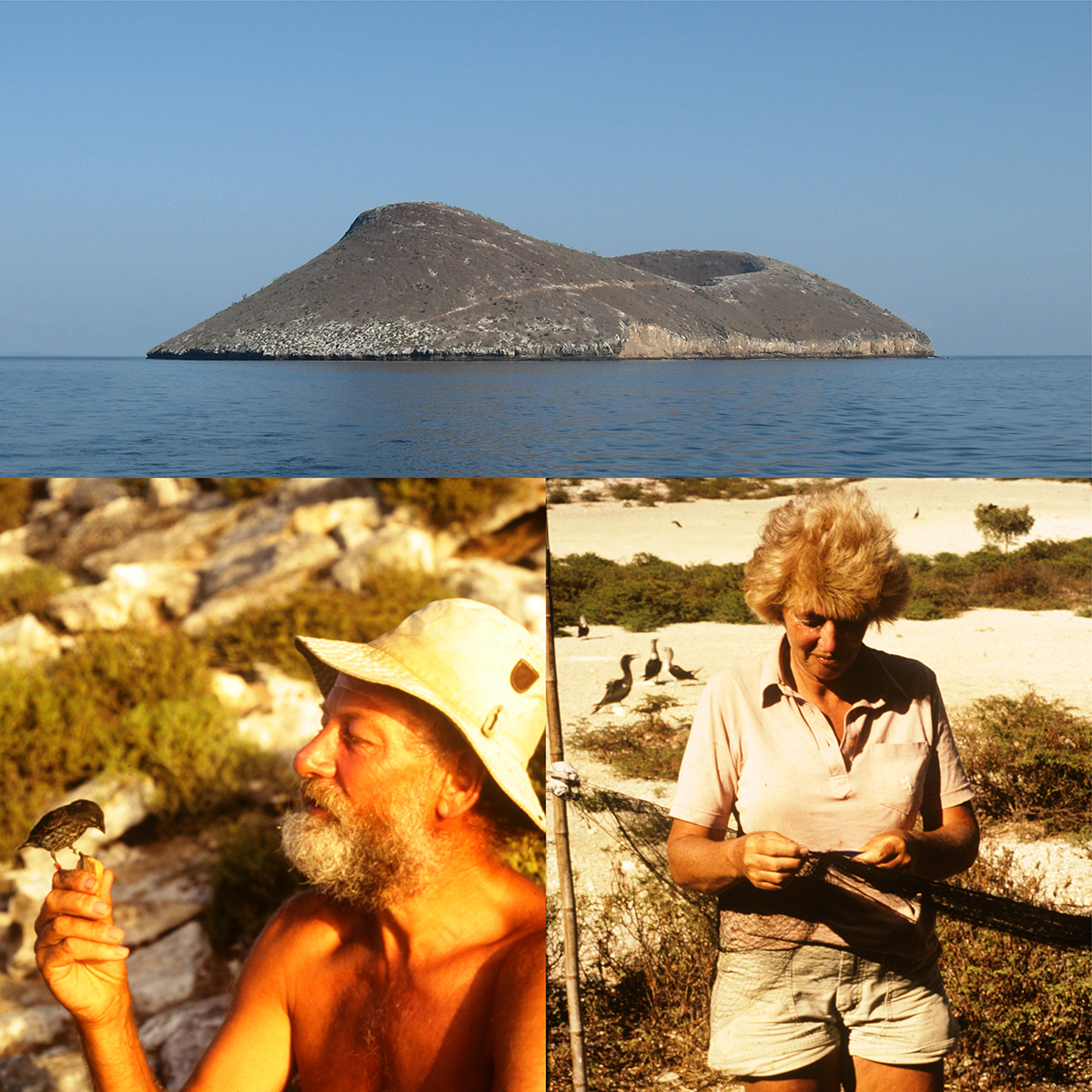

Peter Grant: We were privileged to receive the Kyoto Prize in 2009. At that time, we had been working on problems of evolution of Darwin’s finches on the small island of Daphne in Galápagos for 37 years. We continued that research after the Kyoto Prize for three more years. After 40 years of research, we decided we would synthesize all of our results, and wrote a book called “40 Years of Evolution: Darwin’s Finches on Daphne Major Island” published by Princeton University Press in 2014.

From 2011 to the present time, we have been collaborating with a professor of molecular biology and genomics in Uppsala University in Sweden. His name is Professor Leif Andersson. In that collaboration we have carried on the research at the level of DNA.

Nishimura: The first question I have for you is about the value of long-term research and what it means to explore the connections amongst what look like unrelated things. Could you tell us about your thoughts or approach to research?

Peter Grant: The experience of many people who study ecology and evolution of natural populations tells us that long-term studies inform us much more about normal processes in nature than do short term studies. The reason is that, as time goes on, investigators encounter new circumstances, new problems, and new questions. In the process of answering these new questions, they gain a deeper understanding of the phenomenon they are studying.

That is especially true in an environment like the Galápagos because the weather changes very dramatically from a dry season to the wet season in a year. On top of that, there are strong changes from one year to the next. We have witnessed some very strong perturbations*1 of the normal climatic cycle. Those perturbations or changes take the Galápagos weather into either drought on the one hand, or extremely abundant rainfall on the other hand.

The value of long-term studies is that the more we go on, the more we learn about how these changes in weather conditions affect the animals and the plants. Many people from around the world who study animal and plant populations for a long time say more or less the same as I have just said. The longer they continue, the more they learn; not just extra information of what they already knew, but new information, a new understanding of a system they work with.

Rosemary Grant: We are able to follow individuals over time. We can measure them, take a tiny drop of blood for later DNA analysis, and find out what they feed on, how many offspring they produce, how these offspring survive, and whether those offspring reproduce themselves. So we’re able to get long pedigrees and all the information from individuals. This has allowed us to determine that when there’s a perturbation of the environment, such as a drought, we know how many die, who survived and why they survived.

By being on the island, we are also able to pick up things that are completely unexpected. When we first went to Daphne Island, we didn’t know there was occasional hybridization.*2 People thought there was no hybridization. However, we were able to pick up rare hybridization and follow the evolutionary effect of this. We were also able to study the establishment of a completely new population as a result of an individual coming onto the island, and then follow this new population from its inception over six generations. Now we’re able to do full genome analysis and show the genetic underpinning*3 of all these changes.

Peter Grant: We had to study the finch populations for 17 years in order to find out how long an individual finch can live. They live as long as 17 years, and we had to study them for that length of time to find that out. This is another little example of the value of long-term studies.

Nishimura: I am the type of person that is interested in many different things, and this makes me wonder where you two get the ability to maintain your focus as you keep looking at the same subject at the same place for such a long time. Some might stay at the Galápagos Islands for a year and then go to another place, while others might look at a different subject every time they come to the Galápagos Islands. Why do you think you could maintain your passion for the same single subject?

Rosemary Grant: It started when I was very young. I was interested even as a small child in understanding how species arise, what the variation between species is, and how it came about. I always wanted to answer that question in various ways even when I was at school and then university. So when we had the opportunity to dive into it very deeply, it felt as though it was a huge opportunity to follow up.

So we were following the unexpected to find an answer to the very big questions “how did species arise,” and “what is the variation and how did it come about.” We could answer them from many different angles. For example, from an ecology angle, a genetic angle, or a behavior angle, we were trying to answer different aspects of these big questions. At the same time, however, all sorts of unexpected things happened in the field. Following those leads gave us insight which we didn’t even dream about at the beginning.

Peter Grant: Each of our discoveries leads to new questions. We went from discovery to question, from new findings to another question and so on. Even after 40 years, we never ran out of questions. If we could live to 140 years, we would still be on Daphne asking questions.

Nishimura: There is something that I would like to ask about tackling big questions. When you were faced with big questions, you would have moments of great joy, but sometimes you would also feel anxious, wondering if you can ever find answers. What do you think helped you persevere in carrying those big questions?

Rosemary Grant: You’re absolutely right. This is where not everybody can do everything, certainly neither Peter or I. When asking a question, we could go so far in the field. However, there came a point where we wanted to understand the genetic underpinning of the things we were seeing. We took very small samples of blood for DNA analysis and did some of the analysis ourselves, but only a little bit. So at that point, we had to collaborate with people for more advanced analysis.

The first person we collaborated with was Clifford Tabin and his students at Harvard University. They are developmental biologists and they understood what happens in the embryo itself. With them, we got permission to collect some eggs that they were able to look at. They found out a lot about what was going on in the embryo as it was developing, which affected the morphology of the adult. But we wanted to know more about what was happening in individuals that caused changes we saw in the field.

For that, we later collaborated with Leif Andersson in Uppsala University. He has the techniques to apply to the blood samples we collected from the time that we first began collecting blood samples all the way up to the present. We know what’s happening in the field and he can interpret what’s happening at the genome level. It’s very exciting to put the two together and go back to find the genetic underpinning of all the things that we saw in the field.

Peter Grant: I’d like to say that there are two different types of big questions: that is, big questions which have a single answer and big questions which have lots of partial answers. As an example of the first ones, we can think of the genetic code (*4) that is present in the DNA. How the code is constructed was a major problem a few decades ago. It was solved with some contributions from several people, but finally by Watson and Crick. Then we had a clear answer to what the genetic code was. There is another kind of question which is very broad and large. It’s very difficult to solve, if not impossible, with a single answer. We have been asking a question of that sort. The question is: “how can we explain the origin of biological diversity?”

How can we explain why the world has so many species of organisms, animals, plants, and microorganisms? We chose Darwin’s finches in the Galápagos, 18 species that have evolved in the last approximately one million years, because it was a relatively small unit. But that question of “how can we explain the evolution of 18 species derived from one?” is still a very big and complex question. We have been driven year by year to advance our understanding of that problem without solving it entirely in the way the DNA code was solved.

Nishimura: You two are researchers with different areas of expertise, and yet you have had interest in the same questions and pursue that interest together. It would have played a key role in continuing a long-term study to have someone beside you. Someone who understands what is fantastic about a new finding and what possibilities there are when a new question is answered. Especially, having someone to share the joy with or to celebrate that new finding, wouldn’t it?

Rosemary Grant: I think it played an enormous role in that we had the same interest and each of us came about it from different angles. We were able to bounce ideas off each other. We also acted as almost a brake on each other’s speculations, which would prevent us from going too far ahead of reality. We were constantly checking each other. And of course, when we had a big success, we could celebrate together. So working together was and still is enormously successful and rewarding. I hope there will be many more husband-and-wife teams.

Peter Grant: I would just like to add that you’re right in this respect: it is extremely rewarding when we, as a husband-and-wife team, have jointly faced difficulties and solved a problem. The failure to come up with an answer to a problem and the necessity of putting our minds together to try to solve that problem itself is something to celebrate. But when we succeed in getting an answer to a question which will help us to develop an even deeper understanding of the evolution we’re interested in, then that is truly a big celebration. That success through our joint efforts is definitely a celebratory moment.

Sugimoto: You two are amazing partners in your research, and you are parents and husband and wife at home. I imagine there would have been challenging times for you to be researchers working together in the same field and being a family at the same time.

Rosemary Grant: There were challenges, especially at the beginning, when deciding for me whether to go ahead and do a Ph.D. We were in Montreal at that time and there was no daycare or anything like that. So we decided I should stay at home and have a babysitter for one day a week so that I could spend the whole day in the library keeping up with the journals. It wasn’t until when we moved to the United States and the children were at school that I was able to really get back to fulltime research.

At that time, we didn’t have much money. So I took a teacher’s training course and I taught in a school for two or three years. So I was juggling school teaching, taking care of children and doing research. Fortunately, our children loved to be in the Galápagos. Then things got much better and I was able to publish papers. But I did not get my Ph.D. until I was 49.

But I had a very good supportive husband who supported me all the way. Even when the children were young, I was able to take a day off every Monday to go to the library. Fortunately, there are good daycare centers for young children nowadays. In places like Sweden and Finland, there are two or three years of maternity or paternity leave for children. I think that we now have a better environment for female and husband-and-wife researchers.

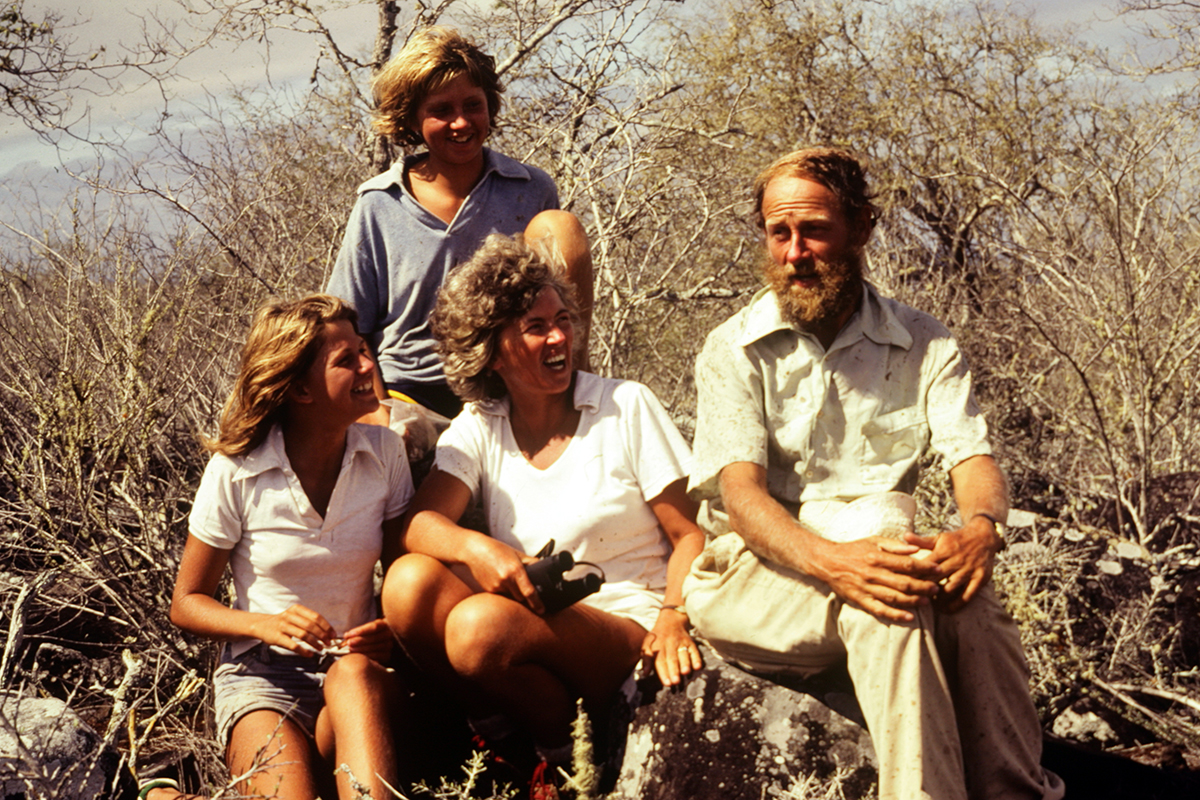

Peter Grant: In 1978, after the 1977 drought, we spent three and a half months on the island of Genovesa in the northeast of the archipelago with our two children, who were 13 and 11. This is where Rosemary did her Ph.D. thesis. Imagine, three and a half months on an uninhabited island, in a remote part of the archipelago with very few tourists visiting, rarely, about one every 10 days. The children had a wonderful time with nature to study, books to read and their schoolwork to do while the parents were able to do research. I look back on that as being the absolute highlight of our family life.

Nishimura: I remember, in your Commemorative Lecture after receiving the Kyoto Prize, Peter mentioned the influence of Professor Evelyn Hutchinson on you when you were at Yale University. I would like to ask you two what your advice would be for young researchers.

Peter Grant: I would hand on the following advice that I was given; to the next generation of research workers and the generation after that. I think there’s a very great value, as Evelyn Hutchinson pointed out, in making connections between very disparate ideas and facts. One way of doing this is to widely read across all intellectual or scholarly disciplines, across the arts and across the sciences, to the extent that we have the time and the ability to do so.

It’s very enriching, not only for our own welfare, but also for helping the scientific process. I think the best way to illustrate it is to suggest a hypothetical example. One might be able to take an idea from admiring the construction of a cathedral and put it in the context of the development of animals, like the beaks of Darwin’s finches.

Another way is to be very deliberate and make connections. Many of these connections will not be very enlightening. However, in some cases, they are really fruitful and you retain them. One that several people have commented upon as being productive is the unconscious way of putting disparate ideas together. It is facilitated by having a very broad reading, but it’s not actually dependent upon it. I’m thinking of an example of someone who wakes up in the morning but is still in a dreamlike state. They suddenly get an image in their mind of putting two things together that they had not previously thought had any relationship.

For example, the German scientist, August Kekulé in the 19th century had a habit of daydreaming. He was puzzling about the structure of benzene. One night, while he was watching the fire in the fireplace, he went into a daydreaming state. When he came out of that state, he suddenly had the image in his mind of a snake that was coiled in a circle and the mouth was biting the tail and he thought “that’s it!” That is the structure of benzene, a ring of six carbon atoms. He achieved it in what appears to be a completely accidental way of putting together two unrelated things, chemistry and snakes.

Rosemary Grant: While he was speaking, I thought of separate examples. The one that actually happened was that our work was taken up by people in cancer research because cancer in the colon and cancer in the lung are analogous to finches on different islands or different ecosystems. We have been invited to spend a week at both the cancer research centers in London and in Texas. In cancer, genes from a cancerous cell in one tissue may be transported in the blood-stream by viruses to cancer cells in another tissue, enter cells and combine with the genes there, causing a virulent metastasis. This is an idea we would like to see explored. In hybridization between different finch species and the mixing of genes in different cancer clones, the same sort of evolutionary responses might occur. It was very exciting to actually discuss these similarities and differences between our research and cancer research.

Introgression*5 between two finch species is very much the same as diasporas in human populations, where different cultures come together. You can get a synergistic response which can cause, on one side, great innovations in music, art, or architecture. The bad side is that it can lead to conflict or war. The same sort of thing is happening in the finches. I think it is up to us humans as intelligent beings to try and cultivate the beneficial cultural side in human affairs: music, art, and architecture, and not the conflict and war side.

Nishimura: You two seem to have had interest in many different things while keeping focus on your research. How do you stay open to, curious and interested in different fields?

Peter Grant: We have the problem of keeping up with the advances in fields that we’re interested in. Yet the fields are expanding so rapidly in knowledge that it’s impossible for anybody to be a generalist like Darwin 150 years ago. So what do we do? We don’t lack any curiosity and interest in a whole variety of things in this world. They remain unaffected.

However, in research, we have to seek help from collaborators in order to pursue different elements of the research program. We simply cannot do everything. Furthermore, outside our actual research, if we have questions that we puzzle about just because we’re interested, we try to either read books or get onto the web to get answers. We also call upon colleagues who work in other areas, for example, conservation biology.*6 We ask colleagues for help in understanding whatever it is that we are puzzled about and which is outside our realm.

It’s the problem of keeping up with an ever expanding knowledge base across the fields of biology, as well as art and literature and architecture. It’s impossible to be specialists in everything. So I’m repeating myself when I say we keep our curiosity up, but we have to seek answers from other people or other sources if we have burning questions that we can’t answer ourselves.

Rosemary Grant: I will just add that keeping up with the ideas and enthusiasms of young people, talking to young people like yourselves, and learning what they are doing or what young people are thinking help us.

Nishimura: Thank you very much.

*1. perturbation An event in which a part of an ecosystem is changed drastically by environmental change such as typhoon, fire, landslide and volcanic eruption, environmental manipulation by human beings, the impact of a particular organism, and so on.

*2. hybridization Breeding among different species or strains.

*3. genetic underpinning Genes that generate specific traits and/or behaviors of organisms.

*4. genetic code The sequence of nucleotides in nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) that determines the amino acid sequence of proteins.

*5. introgression Transfer of part of genes of one species or strain to another by hybridization and repeated backcrossing (crossing within a genetically similar strain).

*6. conservation biology Biology that aims at conservation of ecosystems and biodiversity.

Click below to watch the YouTube video of the message from Dr. Peter Raymond Grant and Dr. Barbara Rosemary Grant at their receiving the Kyoto Prize in 2009.

Previous articles in “Unearthing the Words of Kyoto Prize Laureates”

#1 Dr. Toyoki Kunitake: You’re Sure to Find a Breakthrough in the Process of Going Back and Forth Between “Abstraction” and “Materialization”

#2 Dr. Takashi Mimura: “Being of Service” Means to Be Needed and Appreciated by the Overwhelming Majority

#3 Dr. Takeo Kanade: The Habit of Returning to the Question “Why am I Doing This Research?” Is the Key to Reaching the Essence

#4 Tamasaburo Bando V: It is Only in Our Encounters with Others that We Can Convey the Ineffable

#5 Dr. Graham Farquhar: As Part of An Ecosystem, I Exist as an “Old Tree in a Forest”

#6 Dr. Edward Witten: Science Helps Us Understand the World Better

[About the interviewer]

Yuya Nishimura

Executive Director, MIRATUKU. Earned a Master’s Degree from the Osaka University Graduate School of Human Science. Built a cross-sector -business and -domain innovation platform, supports leading companies (about 30 annually) in creating new businesses, assists launch of R&D projects, designs future visions, and searches for future trends. Other positions include Innovation Designer, Innovation Design Office, RIKEN, Japan, and Specially Appointed Associate Professor, Social Solution Initiative (SSI), Osaka University MIRATUKU website

[About the writer]

Kyoko Sugimoto

Freelance writer. Earned a Master Degree in Media, Journalism & Communication, Graduate School of Letters, Doshisha University. Interviews researchers, business managers, Buddhist monks, urban designers on such topics as asylums, communities, and Buddhism. Authored Kyodaiteki Bunka Jiten: Jiyu to Kaosu no Seitaikei (Kyoto University Cultural Encyclopedia: Ecosystem of Freedom and Chaos), Film Art, Inc. writin’room