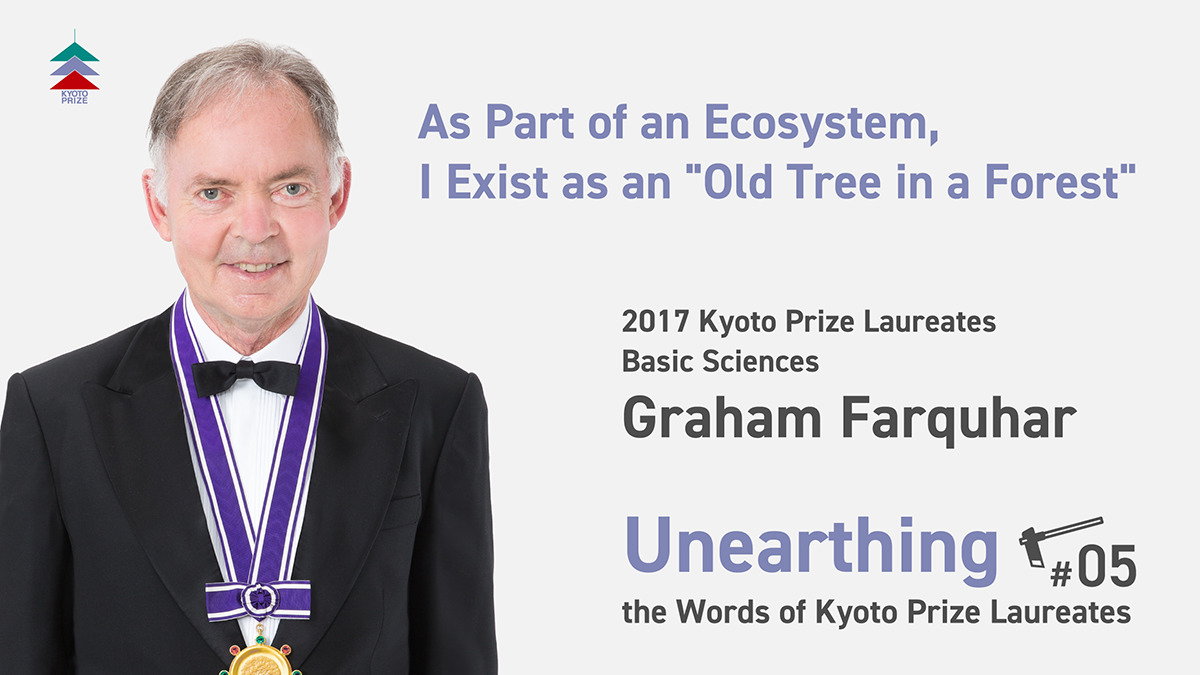

An international award of Japanese origin, the Kyoto Prize is presented to individuals who have made significant contributions in the fields of science and technology, as well as arts and philosophy. Kyoto Prize laureates are those who have made an extra effort to plumb the depths of their chosen fields and profoundly inspired the scientific, cultural, and spiritual betterment of humankind through their achievements. In this series of “Unearthing the Words of Kyoto Prize Laureates,” we will interview the past laureates of the Kyoto Prize and take a closer look at the words that they delivered at their Commemorative Lectures to get to the heart of their unique ideas, thought process, and attitudes as inquirers. In this installment of the series, we were honored to interview Dr. Graham Farquhar, the 2017 Kyoto Prize laureate in the Basic Sciences category.

Previous articles in “Unearthing the Words of Kyoto Prize Laureates”

#1 Dr. Toyoki KunitakeYou’re Sure to Find a Breakthrough in the Process of Going Back and Forth Between “Abstraction” and “Materialization”

#2 Dr. Takashi Mimura“Being of Service” Means to Be Needed and Appreciated by the Overwhelming Majority

#3 Dr. Takeo KanadeThe Habit of Returning to the Question “Why am I Doing This Research?” Is the Key to Reaching the Essence

#4 Tamasaburo Bando VIt is Only in Our Encounters with Others that We Can Convey the Ineffable

──────────────

Graham Farquhar

Plant physiologist. Distinguished Professor at the Australian National University (ANU). After receiving Ph.D. in Biology from ANU (1973), Farquhar published process-based models of photosynthesis in1980. He was awarded the Humboldt Research Award in 2011 and the Prime Minister’s Prize for Science from the Australian Government in 2015. He has been a fellow of the Australian Academy of Science, National Academy of Sciences, and Royal Society. Read more

Nishimura Today, we would like to learn about how you think and look at things, which provides the basis of your research. First of all, may I ask you to briefly introduce yourself?

Farquhar I was born in Hobart, Tasmania, Australia. My father worked as an agricultural extension agent, taking scientific developments to farmers. My mother was a primary school teacher until I was born. My grandparents on both sides of the family came from the land; my grandfather on my father’s side was a miner, but he also farmed with my grandmother. My grandparents on my mother’s side owned various machines for farming and were helping others with farmwork on a contract basis.

The reason why I told you about my family’s background is because I believe that behind my wish to be of use to farmers and the agriculture field are my family’s deep ties to the land and agriculture.

Sugimoto Your father was a scientist in the field related to agriculture, too. Did that influence you when you chose to pursue a career as a researcher?

Farquhar In 1956, when I was nine years old, my father took a job in the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO),*1 so we moved to Melbourne. Then in 1958, we moved to New York in the U.S. and spent two and a half years there as my father did a Master’s degree and then a Doctorate degree in Agricultural Education at Cornell University. After that, we returned to Melbourne.

When I was fourteen, my father told me that there was a new, exciting discipline called biophysics, and from that point on, I wanted to become a biophysicist despite not knowing what biophysics really was. On the advice of Dr. Ralph Slatyer, then a leading CSIRO scientist, I studied physics first and then picked up biology.

In 1965, I enrolled at Monash University, but when my family moved to Canberra, I was transferred to the Australian National University (ANU) for third-year physics and mathematics. Then in 1969, I began studying biophysics and applied for a scholarship offered by the University of Queensland and won 1,500 Australian dollars. With this scholarship, I was able to live and conduct research somewhat independently. Another lucky event that occurred that year was that I saw a performance by the Bolshoi Ballet,*2 which introduced me to the world of dance.

Nishimura Dr. Farquhar, you may be talking rather slowly in consideration for us. If you feel more comfortable speaking at a faster pace, please do so.

Farquhar I speak slowly because it’s a characteristic of my family’s farming background. Also, by speaking slowly, my brain can keep a little ahead of my lips.

Nishimura How the speed of speaking relates to the speed of thinking is very interesting. As an experienced dancer, do you think the rhythm of dance has something to do with the rhythm of thought?

Farquhar That’s a very interesting question. It’s true that in dance you have to be quick and I tend to move slowly. I did have some difficulty keeping up with female dancers.

I always felt that science and the arts are complementary, and dance is no exception. Some things are similar. One thing is that you have to be creative, and in both cases you have to do a lot of practice. As you say, “Genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration,” and I think this applies to both the arts and science. In terms of the roles of leaders, too, the roles of an artistic director in a ballet company can be compared to those of the head of a laboratory in a scientific setting.

Some of the best ballet teachers are not very good verbally but marvellous at demonstrating with their hands and body. So, they communicate in other ways than language. To an extent, that’s true of scientists as well. I think scientists use the language of mathematics a lot, and by doing so, they use tools other than language to communicate.

Nishimura I see. It’s not a matter of whether you use language or not; instead, it’s important to create an expression that can be understood. And I think that this is exactly what your mathematical model does. My question is, how does creating an expression that can be used by many people benefit the world?

Farquhar Making things accessible to many people can contribute to the advancement of the world, but there are two sources of tension there, so to speak: The first kind of tension is caused when you try to write something with both precision and simplicity, as these are often two contradictory goals.

The other kind of tension is created by the desire to seek recognition by impressing others, which is not so nice. For example, when I finish writing a very simple and easy to understand paper, I’m tempted to boast of my knowledge and accomplishments by quoting complicated mathematics in the appendix. There’s really no need to do that, but it’s hard to resist the temptation to include it.

People tend to respond to things that are simple and easy to understand. A good example is artificial intelligence (AI), which appears very simple, but is based on extreme complexity which nobody understands. Its deceptive simplicity makes me frightened about the ongoing move to use AI for military acts and making judicial judgments.

Nishimura The process-based photosynthesis model that you developed not only helped to deepen our understanding of plants’ photosynthesis but also applies to the elucidation of climate change. I’d like to ask you about the simplicity that may be applied to a broad range of fields, as seen in this case.

Farquhar I think there is a distinction in English between that which is simple and simplicity, and I believe that the latter involves beauty. In the world of fundamental physics, for example, you often encounter a beautiful mathematical equation that possesses simplicity.

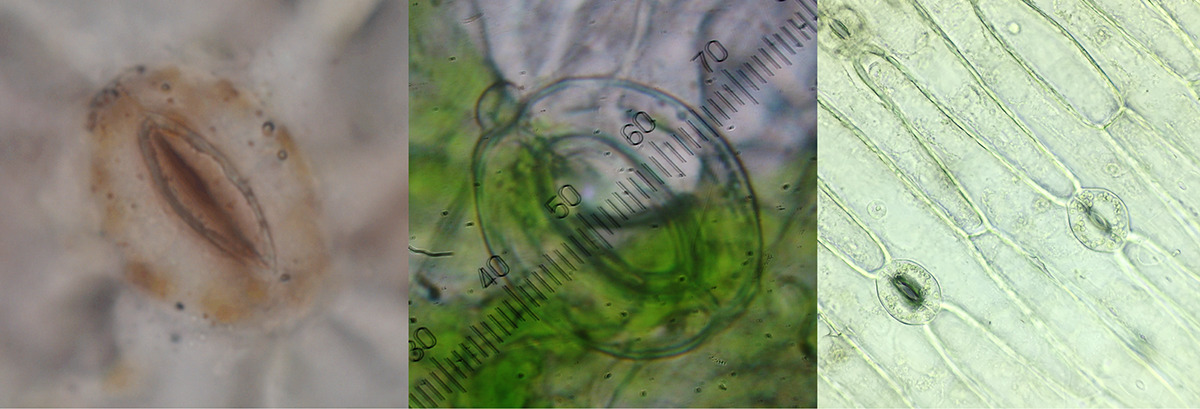

Of the equations I have come up with, one that is very simple is PδA=NδE, where, with regard to the water use of plants’ stomata, the positive benefit in terms of increased CO2 assimilation rate (PδA) is equal to the negative benefit in terms of increased transpiration rate (NδE). Furthermore, this equation expresses the process-based model of photosynthesis by a single leaf and so can express everything about the canopy.*3 One of my friends made a tapestry with this equation designed in it, and it expresses true beauty.

I must say, it’s beautiful to see that a very simple and short equation has applications beyond our imagination and renders a multitude of phenomena predictable. In retrospect, I’ve been very fortunate to encounter such a beautiful equation in my research, while so many scientists must deal with very complicated equations and push through their research. May I expand on how other researchers and I created an equation from a theory on plants’ assimilation of CO2?

Nishimura Yes, please. I’d love to hear the story in detail.

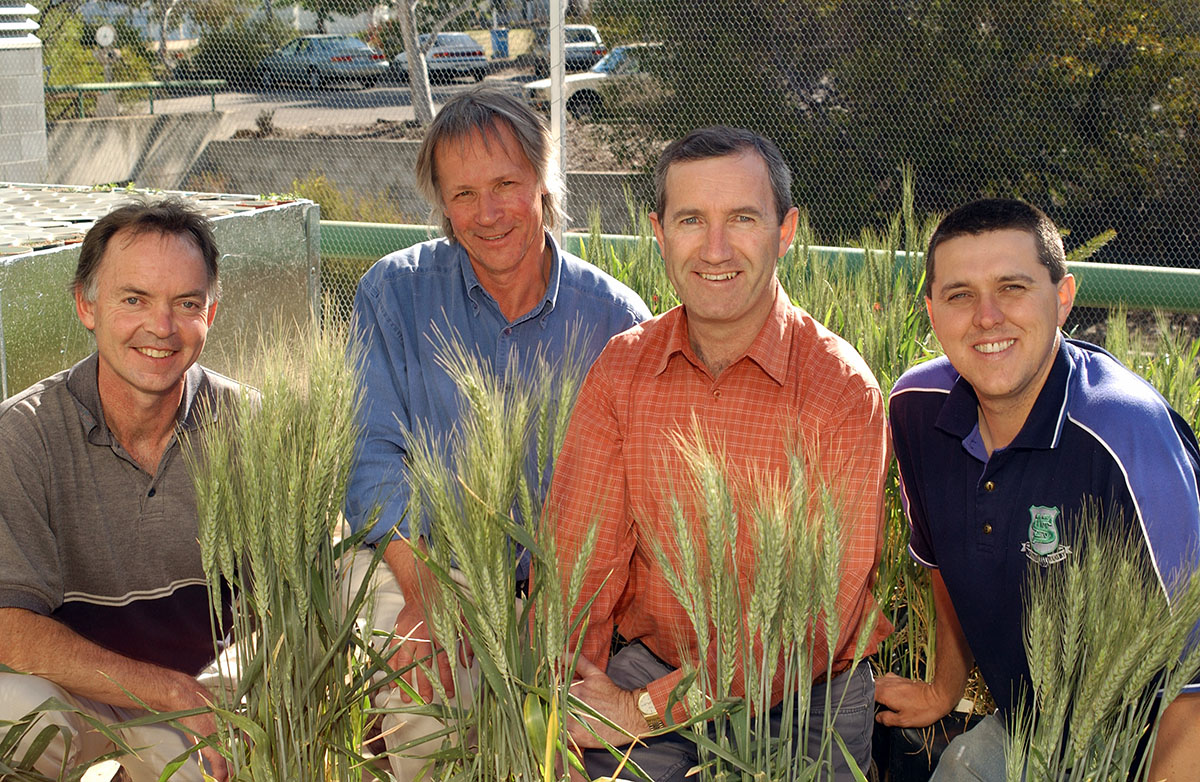

Farquhar In around 1980, I ran into Richard Richards whom I had known in my high school days. He has long been a wheat breeder at CSIRO. At that time, he was conducting research to screen different wheat genotypes to discover ones that had high water-use efficiency, and so he kept a stock of dried leaves. He had measured how much growth the different plants had achieved per unit of water evaporated by the plants. I had been developing a theory that differences in water-use efficiency should be reflected in the carbon isotopic composition of the leaves. We took the liberty of using his dried leaves to measure carbon isotope ratios. The data thus obtained matched the theory.

Our idea in the form of an equation that came from something inside our mind somehow matched a practical framework that involved real plants. and human activities such as growing the seeds, harvesting and burning the leaves to measure carbon isotope ratios and water-use efficiency, and eventually releasing new varieties. The moment when the mathematical model constructed in our minds came to intersect with reality was nothing short of magical.

Nishimura If the magical moments you’ve experienced—the joy and beauty that come with them—share something with the joy and beauty you feel when you dance, what words would you use to describe them?

Farquhar It’s purity, a clean feeling, an excitement, or walking in unexplored areas. Be the first to experience something, but that may not be so clean because it is a little bit competitive to be the first.

Perhaps the experiences of athletes that are going to be performing in the Olympic Games are similar to what we scientists experience. Just as athletes build their physical strength to break records, scientists exercise their minds to get the best results and value being the best in the most creative and honest manner.

Nishimura I’m curious to learn more about what you mean by the feeling of “honest” and “clean.”

Farquhar Before I answer that question, can I ask Ms. Sugimoto a question? As a writer, you must have the same experience when you write something. When you polish your writings and make up beautiful sentences and paragraphs, like peeling an apple and removing every last blemish, do you not have a similar experience?

Sugimoto You’re right. And it may not merely be about polishing sentences and paragraphs. For example, I am listening to your insights today, so I’m eager to focus on two things for my writing: to capture the essence of what you value most in your life and to convey it in the simplest words to the readers.

Farquhar Building on Ms. Sugimoto’s thoughts, a clean feeling is the one you have when you have composed a sentence or expression that contains nothing less or more than the bare essence. In our everyday lives and the real world, there are all sorts of complications and noises that may not be necessary. Being clean is the state you reach when you scrub your attention to remove unnecessary things and express nothing but your main idea.

To answer Mr. Nishimura’s question about being honest, perhaps I can give you an example. Some plants like sunflowers move their leaves during the day to follow the sun. Other plants move their leaves edge-on to stop water loss, because too much sunshine can affect their water use. As I worked on plants’ stomata, I was convinced that the CO2 concentration inside the leaves was related to the angles of leaves’ movements, knowing that stomata close when there is more than enough CO2, and made a hypothesis.

My American colleagues were responsible for experiments to verify this hypothesis, and I remember betting dozens of bottles of beer that the CO2 concentration changes the angles of leaves. But it turns out that the CO2 concentration is not directly related to the angles of leaves, as it is not a central element in this phenomenon.

Fortunately, I hadn’t published a paper on this hypothesis. If I published the paper without actually really testing my hypothesis, that would have been dishonest. In other words, honesty demands that you actually try possibilities and check their results before you waste people’ time.

Sugimoto In your Kyoto Prize commemorative lecture, you mentioned so many members of your family, friends, fellow researchers, and Dr. Ian Cowan and other mentors, which impressed me profoundly. Your research topic of photosynthesis is the foundation of the ecosystem, and I assume you have dearly cherished your ecosystem as a researcher and an individual, including the bonds with your mentors and colleagues as well as with people close to you. I wonder how you have thought of the ecosystem of your research work over time.

Farquhar Your observation is certainly correct. My family and certain colleagues have had an enormous impact on me, and I have been lucky to have them in my life.

The ecosystem is constantly exposed to a myriad of threats. It is a constant fighting to stay vibrant as an ecosystem without being eroded by invasive species. But then there is the question of whether every invasive species is a genuinely unwanted weed. One might argue that it’s time for old species that have long survived to leave and need to make way for new species. It’s a question of “whether we should accept changes as inevitable.”

Needless to say, the truth lies somewhere between “regarding invasive species as a threat” and “accepting changes as inevitable.” The same can be said if you think you are part of a certain ecosystem.

In practice, I’m trying to work with young people, as well as older researchers, which is enjoyable and a different kind of challenge. Some ecosystems are very stable and last a very long time, while others are very transient. The fact is, if you’re used to one ecosystem, it’s tough to see your own ecosystem eroded by invasive species.

Living in the bush in Australia, we witness constant threats from resilient invasive weeds and wild animals. However, Eucalypts replaced other trees like Nothofagus,*4 some of which are on the verge of extinction. If you think this way, it’s very difficult to say what is absolute. As part of a certain ecosystem, I feel a bit like an old tree in a forest.

Sugimoto What do you specifically mean by “an old tree in a forest?”

Farquhar In Australia, nearly all old trees get attacked by white ants. They attack the trees from the roots and hollow out the trunk, so old trees are perceived to be vulnerable as they tend to be knocked down by heavy rain or wind. But, of course, some of these big trees are strong and durable. In Tasmania, where I was born and raised, some old trees are as tall as 100 meters or more. These trees seem so powerful, and it’s hard to imagine them getting knocked down, and they seem like they will endure for years to come. When I say an “old tree,” I mean both—vulnerability and strength.

Sugimoto So, as a scientist who is an “old tree” that has studied plants for many years, what are some of the wishes you have for the future of this world?

Farquhar I think we would be so much better off if everyone, including myself, tried harder to be honest and creative. It’s so easy to let the media do the thinking for you or take what others tell you without confirming the facts for yourself. We need to go through the process of slowing down and confirming views we hear on television or in magazines. It might save a lot of the grief the world is experiencing now.

I think we’ve got to be more willing to allow governments and large organizations to make mistakes. I don’t mean deliberate mistakes or something illegal. I mean, leaders have to try out solutions to national and international problems, and mistakes are inevitable in this process.

We are liable to be tough on leaders of big organizations, politicians in particular, when they take big risks and fail. In science, however, failures and mistakes are part of the research process. I wish we could recognize that in being creative, there’s a good chance of things not working, and we have to extend this generosity in science to other fields.

Nishimura Thank you very much, Dr. Farquhar, for answering our questions and giving us so much of your time.

Farquhar My thanks to the two of you for asking such intelligent questions and the interpreter for doing an excellent job.

Nishimura Thank you very much again for allowing us to interview you today.

*1. Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) The largest integrated research institution in Australia with more than 50 sites in Australia and overseas. It covers a broad range of research areas, including agriculture, information and communications, materials, and energy.

*2. Bolshoi Ballet One of the leading classical ballet companies in Russia based at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow. Known for giving the very first performance of Swan Lake composed by Tchaikovsky

*3. canopy The uppermost branches of tall trees in a forest, forming a layer of foliage exposed to the sunshine.

*4. Nothofagus Forest trees commonly known as “southern beech.” Nothofagus species are only found in the Southern Hemisphere including Australia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, and some parts of South America. In Australia, Nothofagus have been threatened with extinction due to the deforestation, wood harvesting and plantation of timber trees including Eucalyptus.

Click below to watch the YouTube video of Dr. Farquhar’s Commemorative Lecture from 2017.

Previous articles in “Unearthing the Words of Kyoto Prize Laureates”

#1 Dr. Toyoki KunitakeYou’re Sure to Find a Breakthrough in the Process of Going Back and Forth Between “Abstraction” and “Materialization”

#2 Dr. Takashi Mimura“Being of Service” Means to Be Needed and Appreciated by the Overwhelming Majority

#3 Dr. Takeo KanadeThe Habit of Returning to the Question “Why am I Doing This Research?” Is the Key to Reaching the Essence

#4 Tamasaburo Bando VIt is Only in Our Encounters with Others that We Can Convey the Ineffable

[About the interviewer]

Yuya Nishimura

Executive Director, MIRATUKU. Earned a Master’s Degree from the Osaka University Graduate School of Human Science. Built a cross-sector -business and -domain innovation platform, supports leading companies (about 30 annually) in creating new businesses, assists launch of R&D projects, designs future visions, and searches for future trends. Other positions include Innovation Designer, Innovation Design Office, RIKEN, Japan, and Specially Appointed Associate Professor, Social Solution Initiative (SSI), Osaka University MIRATUKU website

[About the writer]

Kyoko Sugimoto

Freelance writer. Earned a Master Degree in Media, Journalism & Communication, Graduate School of Letters, Doshisha University. Interviews researchers, business managers, Buddhist monks, urban designers on such topics as asylums, communities, and Buddhism. Authored Kyodaiteki Bunka Jiten: Jiyu to Kaosu no Seitaikei (Kyoto University Cultural Encyclopedia: Ecosystem of Freedom and Chaos), Film Art, Inc. writin’room